Written by Dazai Osamu and published in February 1935 as the third part of Retrogression. Translated by A L Raye.

Original text: https://www.aozora.gr.jp/cards/000035/files/260_34634.html

I was not trying to imitate a foreign style duel. I literally just wanted to kill him, and my motive for doing so was quite superficial. It wasn’t like he was exactly the same as me in every way, and so we hated each other from the bottom of our hearts because the world didn’t need two of our kind; nor was it because he was my wife’s former lover, and that he was always constantly walking around talking to the neighbours in scientific, explicit detail about their frequent affairs. In fact, my opponent was just a young peasant wearing a dog fur jacket who I met for the first time that night at a café. I stole his drink. That was the only motive.

I am a high school student from a northern castle town. I like to go out and have a good time, but I can be rather stingy when it comes to money. If I was patient, then by just puffing on my friends’ cigarettes and going without haircuts I could save up five yen, and with it I would sneak out into town by myself and spend every last penny. In a single night out, I would never spend any more or any less than five yen. In any case, I always seemed to get the most out of that five yen. First of all, I would exchange all the loose change I’d saved for a friend’s five yen note. If the note was new enough to cut my hand then my heart would beat even faster. Then I would carelessly thrust it into my pocket and hit the town. I lived only for the sake of these monthly or bi-monthly outings. At the time, I was being tormented by an inexplicable depression. An absolute loneliness accompanied by an all-consuming scepticism. It’s disgusting to say it out loud! Maupassant, Mérimée, and Ōgai seemed more real to me than Nietzsche, Villon, or Haruō. I dedicated my life to those five yen pleasures.

Even if I went to a café, I never showed any enthusiasm. I acted as though I was tired of playing around. If it was summer I asked for a cold beer and if it was winter I asked for hot sake. I wanted to give people the impression that my drinking was just a seasonal thing. Appearing reluctant, I took no notice of the beautiful waitresses while mulling over my sake. In every café there is always at least one middle-aged waitress who made up for her lack of allure with an insatiable avarice, but I spoke only to those kinds of waitresses. We mostly chatted about the weather or the general cost of living. I was skilled at counting the number of empty bottles, with a speed even God couldn’t keep up with. When the number of beer bottles lined up on the table reached six, or sake bottles reached ten, I would casually stand up as if only just remembering something and softly mutter ‘Check please.’ The final total never exceeded five yen. I would deliberately thrust my hand into each and every pocket as though I had forgotten where I had put my money. Eventually I would find it in my trouser pocket. I would let my right hand grope around inside the pocket for a while to make it look like I was selecting from between five or six different bank notes. Finally, I pull out the single banknote from my pocket and, after pretending to confirm whether or not it is a ten yen note or a five yen note, I hand it over to the waitress. As for the change, I’d leave it behind without even glancing at it, saying ‘It’s not much.’ Hunching my shoulders, I would march away from the café until I reached my school dormitory, never once looking back. The very next day, I would once again start saving up every penny of loose change.

On the night of the duel I went to a café called The Himawari dressed in a long navy blue cape and a pair of pure white leather gloves. I never went to the same café twice in a row because I was afraid that my convention of always producing a five yen note would arouse suspicion. The last time I visited The Himawari was two months ago.

Lately, a young foreigner who bore some resemblance to me was beginning to make it big as a successful movie star, and it was for this reason that I too was starting to gradually attract the female gaze. When I sat down at a chair in the corner of the café all four of the waitresses who worked there, each wearing a different style of kimono, came and stood in a row in front of my table. It was winter, so I asked for hot sake. Then, looking as though I was utterly freezing, I shivered. My resemblance to the movie star benefitted me directly when, even though I didn’t say anything, one of the young waitresses offered me a cigarette.

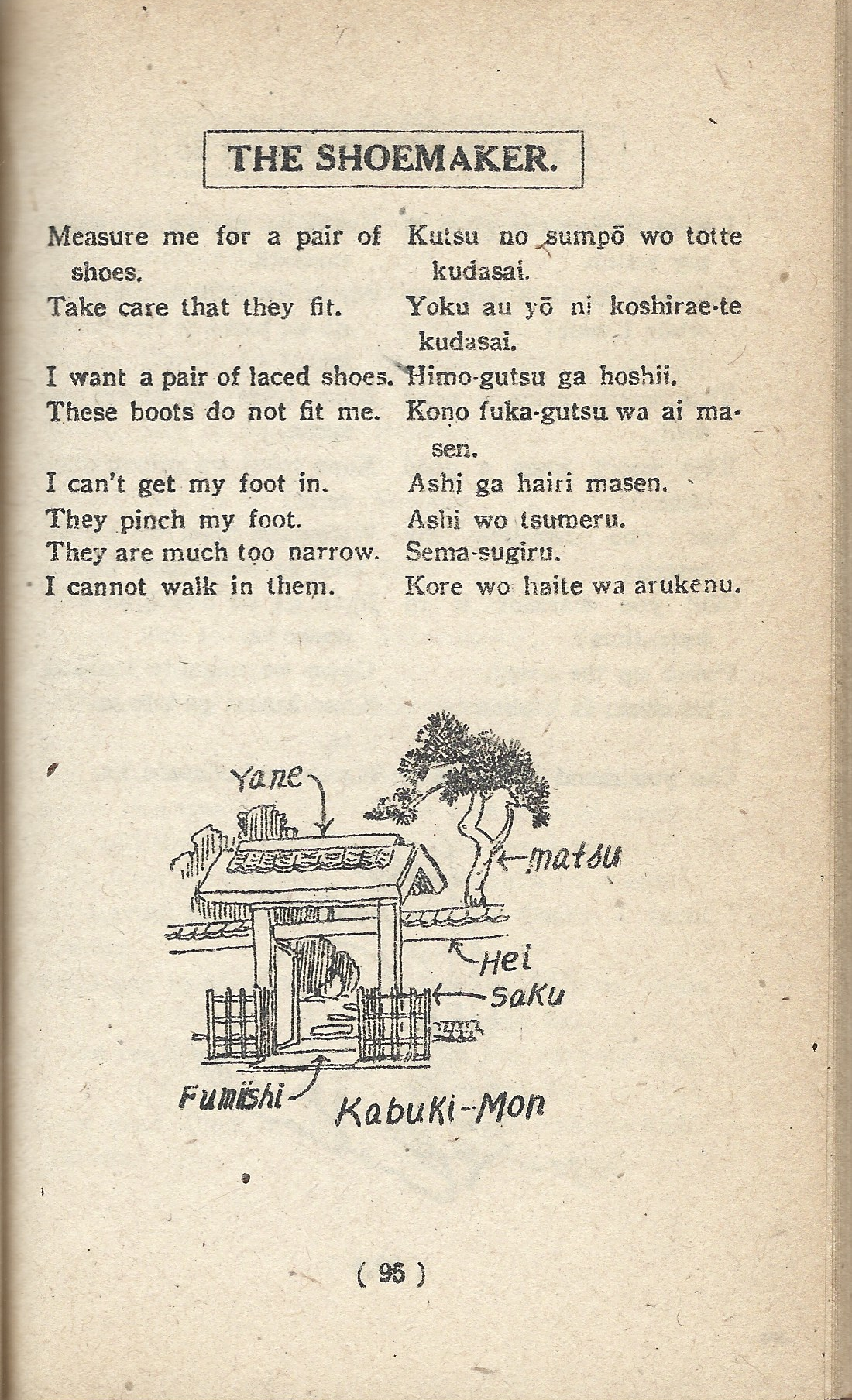

The Himawari was not only cramped but dingy too. On the right-hand side of the wall hung a poster of a woman with her hair done up in a bun who languidly rested her one-foot-by-two-foot face on her hand, her smile revealing teeth as large as walnuts. The bottom edge of the poster had ‘Kabuto Beer” printed across it in black letters. Facing it on the left-hand wall hung a mirror around 10 metres across and mounted in a gold-coated frame. Grimy red and black striped muslin curtains had been hung over the entrance. Above them, a photograph had been pinned to the wall of a laughing Western woman reclining naked on the grass by the edge of a pond. On the opposite wall, just above my head, hung a paper balloon. The lack of harmony was utterly infuriating. There were three tables and ten chairs. A heater sat in the middle of the room. The dirt floor had been boarded over. I knew there was no way I would be able to relax at this café, though luckily for me the lights were dim.

That evening, I received an unusually warm welcome. Once I had finished the first bottle of sake, poured for me by the middle-aged waitress, the younger waitress from before who had offered me a cigarette suddenly thrust her right palm under my nose. Unfazed, I slowly raised my head and gazed deeply into the girl’s eyes. ‘Tell me my fortune’ they said, and immediately I understood. Even if I kept silent, an air of prophecy emanated from my body. Without touching her hand, I gave her a glance and murmured ‘Yesterday, you lost your lover.’ I had hit the mark and, consequently, an evening of unusual entertainment commenced. An exceptionally stout waitress even called me ‘Sensei’. I read everyone’s palms: ‘You are nineteen years old’, ‘You were born in the year of the tiger’, ‘You long to obtain the perfect man’, ‘You love roses’, ‘Your pet dog has had six puppies.’ I was right every time. When I told the middle-aged waitress, a slim and bright-eyed woman, that she had lost two husbands, she swiftly lowered her head. Out of everyone these strange precognitions excited me the most. By this time, I had already emptied six sake bottles. It was then that the young peasant wearing a dog fur jacket appeared at the entrance.

He sat down at the table immediately next to mine, his furry back facing me, and ordered a whiskey. The dog’s fur had a mottled pattern. As soon as he arrived, the heavenly excitement at my table faded in an instant. I began to get pangs of regret for having drunk six bottles already. I wanted to get even more thoroughly drunk. I wanted to extend the joy of this night for as long as possible. The four remaining bottles were just not enough, not enough at all. I should steal his. Yes, I’ll steal his whiskey! The waitresses would never think I did it because I needed the money, they would just see it as some eccentric fortune teller’s joke and, on the contrary, they would probably cheer for me, wouldn’t they? The peasant would also allow himself a wry smile at this drunkard’s prank. So I stole it! I reached out my hand, grabbed the whisky glass on the neighbouring table, and calmly knocked it back. There was no cheering. The room fell silent. The peasant turned towards me and stood up. ‘Outside. Now.’ He said, and started walking towards the exit. I followed after him, grinning. As I passed by the gold-framed mirror I caught a quick glimpse of myself. I looked every part the suave, handsome gentleman. In the depths of the mirror the woman’s one-foot-by-two-foot smiling face peered back at me. I regained my composure and, filled with confidence, flung open the muslin curtains.

We came to a stop beneath the square lantern that hung above the entryway with ‘THE HIMAWARI’ written on it in yellow romaji. The four white faces of the waitresses floated in the dim light of the threshold. Our argument began as follows:

‘Don’t treat me like a damn fool!’

‘I wasn’t treating you like a fool! Come now, I was just behaving like a bit of a spoiled brat. It’s no big deal, right?’

‘I’m a hardworking man. Spoiled brats just make me angry.’

I took another look at the man’s face. He had short cropped hair, a small head, a pair of sparse eyebrows, sanpaku eyes with single eyelids and dark, almost black, skin. He was a solid 15 centimetres shorter than me. I resolved to keep teasing him to the bitter end.

‘Listen, I just wanted to drink some whiskey, since it looked so delicious.’

‘I wanted to drink it too, you know! Whiskey isn’t cheap, and that’s all there is to it.’

‘You’re an honest guy. That’s so cute.’

‘Don’t be a smartass! You’re a high school kid, right? You make me sick, having the nerve to daub all that powder on your face!’

‘On the contrary, I am something of a fortune teller. A prophet, if you will. I bet you’re surprised!’

‘Stop pretending to be drunk. Get on your knees and apologise!’

‘In order to understand me then first and foremost you’re going to need courage. That’s a great phrase, isn’t it? Look at me, I’m Friedrich Nietzsche!’

I waited eagerly for the waitresses to intervene on my behalf, but instead all four of them stared at me coldly while they waited for me to get beaten up. Then I got punched. His fist came flying at me from the right-hand side, and I swiftly ducked my head. Thrown about twenty metres away, my white-striped student cap had taken the blow in my place. Smiling, I started slowly and deliberately walking over to pick up the hat. There had been sleet for the last few days so the slush on the road was very slowly melting. As I crouched down and picked up my mud-smeared cap, I considered making a break for it. I’d still be able to use my five yen, and have another round at a different café. I ran for two or three steps, slipped, and fell flat on my ass. I must have looked like a trampled tree frog. This sorry state of mine made me a little angry. My gloves, jacket, trousers and even my cape were covered in mud. I very carefully got up and, with my head held high, turned back towards the peasant. He was flanked by the waitresses, who were standing guard over him. I didn’t have a single ally to fight in my corner. This particular fact aroused my wrath.

‘I really must thank you.’

After saying this to him with a contemptuous smile, I took off my gloves, and my even more expensive cape, and threw them into the muddy slush. I was pleased with myself for this slightly old-fashioned remark and gesture. Somebody stop me!

The peasant shrugged off his dog fur jacket, handed it over to the pretty waitress who had given me a cigarette, and then slipped one hand into the front of his kimono.

‘No dirty tricks, now!’

Warning him thus, I braced myself.

From inside his kimono he drew out a long silver flute which sparkled in the lamplight. This was handed over to the middle-aged waitress who had lost two husbands.

I was utterly enthralled by this peasant’s integrity. This wasn’t fiction; truly, I wanted to kill this man.

‘Let’s go!’As I shouted this, I kicked with all my might towards the peasant’s shins with one muddy shoe. I was going to knock him down, then gouge out those limpid sanpaku eyes; but my filthy foot hit nothing but air. I became aware of my own ineptitude, and it made me feel miserable. A faintly warm fist hit me right between my left eye and my stuck-up nose. Bright red flames erupted in my vision. I gazed at them. Then, I pretended to stagger. An open palm slap hit me straight between my right earlobe and my cheek and I fell forwards into the mud. In that same moment, I instinctively bit down on the peasant’s leg. It was as solid as a rock. It was like one of those aspen posts you see by the roadside. As I lay face down in the mud I knew now was the time to cry, but even though I desperately tried to weep and sob, alas, not a single tear fell.

The above story is included in Retrogression, our first publication that follows Dazai’s attempt at the Akutagawa Prize through stories, letters and diary entries. The published version has multiple footnotes with cultural information and references, including recently rediscovered and previously lost poetry Dazai wrote in a Bible during his time in Musashino Hospital.

Please help support Yobanashi Cafe and pick up a copy of Retrogression. Our translations will always be free, forever, but if you enjoyed reading this and have the means then please consider purchasing the full book. You can also support us by sharing on social media. Thank you!